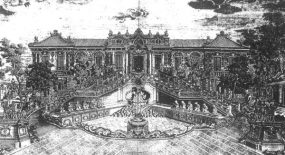

A Childhood at Versailles consists of the first 5 chapters of the memoirs of Mme de Boigne (1781-1866), née Adèle d’Osmond, who was a French salon hostess and writer. She was born in the Château de Versailles and lived at the court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette until her family fled to England during the Revolution. Later in her long life, she married a rich soldier of fortune 30 years her senior, hosted a brilliant salon in Paris, and became an intimate of the last French queen, Marie-Amélie, consort of King Louis Philippe (r. 1830-1848). Childless herself, Mme de Boigne addressed her memoirs to her nephew. The memoirs were not published until 1907, under the title Récits d’une tante, or An Aunt’s Tales. They’ve never been published in English, as far as I know, so I’ve decided to translate the first 5 chapters, the ones that take place mainly at Versailles, and post them here on this blog for interested readers to enjoy for free.

The chapters are quite lengthy, so I’ve broken each one into several parts. In Part 1.6, Mme de Boigne describes the influence of Mme de Polignac and her coterie on the Queen, and also gives us brief pen portraits of her royal siblings-in-law.

Chapter One, Part 6 (1.6)

Mme de Polignac was much more fatal to her. This was not because she was a bad person, but she was indolent and little wit; she intrigued out of weakness. She was dominated by her sister-in-law, the Comtesse Diane, who was ambitious, as disorderly in her morals as she was greedy, and who wanted to win all possible favour for herself and her family. She was tyrannized by her lover the Comte de Vaudreuil, a man as frivolous as he was immoral, and who, using the Queen as a tool, pillaged the public treasury for himself and his companions in dissoluteness.

He made scenes to Mme de Polignac whenever the satisfaction of his demands suffered some slight delay. The Queen would find her favourite in tears and immediately busy herself to have his demands met. As for her own fortune, Mme de Polignac, without asking too much, limited herself to accepting nonchalantly whatever favours the intrigues of the Comtesse Diane produced, and the poor Queen vaunted her disinterestedness. She believed in it, and loved her sincerely. On her side, her confidence was without limit for some years.

M de Calonne’s appointment restricted it somewhat. He was one of Mme de Polignac’s intimates, and the Queen did not want a member of the King’s council to be caught up in that cabal. She said so out loud, but the Polignac coterie, preferring first and foremost a comptroller-general of like mind, highlighted the benefits that would accrue to the Comte d’Artois himself. It was indeed through him that M de Calonne was appointed, despite the Queen’s repugnance. She nursed some discontent from this, which cooled her towards Mme de Polignac, and all of M de Calonne’s eagerness to please her failed to restore him to her good graces. Nonetheless, he replied to her one day when she made a request of him: “If what the Queen desires is possible, it is already done; if it is not possible, it will be done somehow.” Despite such politic words, the Queen never pardoned him.