Today we bring you Part 4 of the War of the Spanish Succession. In Part 3, we saw that war was officially declared on France and Spain by England, the United Provinces (today’s Netherlands), and Austria in the spring 1702.

The States of Europe Take Sides

In the beginning, France and Spain faced Europe alone. They were soon joined by Bavaria, whose Elector still believed that his late son, Prince Joseph Ferdinand, the designated heir to the Spanish throne in the late 1690s, had been poisoned by Austrian agents. The Elector of Cologne also signed on. The last addition to the team was Savoy. It should perhaps be explained that the duchy of Savoy was an independent state at this time. Its duke also possessed the principality of Piedmont and ruled from its capital, Turin. The Duke of Savoy was more or less obligated to support France and Spain because one of his daughters was married to the Duc de Bourgogne, third in line in to the French throne as the eldest grandson of Louis XIV, and another daughter was married to Bourgogne’s younger brother, the newly minted Felipe V of Spain. Savoy was an unreliable ally, however. Nancy Mitford remarks in her biography of Louis XIV, The Sun King, that Duke Vittorio Amadeo was famous for never finishing a war on the same side that he started on. On the whole, it was an underwhelming team. Apart from Savoy’s unreliability, there was the problem of Spain’s near bankruptcy and general weakness. The Elector of Bavaria was a solid ally, but lacked resources. Cologne, of course, was too insignificant to make much of a difference. France would have to shoulder most of the financial and military burden itself.

Those who have been following this series from the beginning will recognize the map below because I used it in Part 1. It may be helpful here in Part 4, too, so I’m reproducing it again.

Europe in 1700. Credit: Wikipedia.

On the other side, the Grand Alliance, as the England-United Provinces-Austria axis called itself, was joined by Portugal, Brandenburg-Prussia, Hanover, and various other German states, the most important of which was the Palatinate (German: Pfalz), a Rhineland state on the French border that was coincidentally ruled by another branch of the Bavarian ruling dynasty. The Palatinate, to the horror of Louis XIV’s sister-in-law, a Palatine princess, had been devastated by French armies in a prior war and was itching for revenge. It was more or less understood that Austria would supply most of the military muscle on the continent while England and the United Provinces would provide sea power.

The Theatres of War

In the beginning, there was actually no fighting in Spain itself. In the words of the English historian Lord Chesterfield (as reported by Will and Ariel Durant in their The Age of Louis XIV, from which I’ve gleaned many of these details), Felipe V was “quietly and cheerfully received” in his new kingdom. Spain seemed so secure that Felipe felt able to spend 9 months in 1702 touring Sicily and Naples, the other kingdoms he had inherited from Carlos II.

The initial fighting was in northern Italy, in Milan and Mantua, which Prince Eugene had already almost overrun on behalf of the Emperor even before the war was officially declared. Other fronts opened up in Flanders and southwestern Germany. The latter 2 regions were the least able of all the theatres of the war to withstand its hardships since both had been battlegrounds for several prior wars going all the way back to the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

Early Reverses for France

Louis XIV, so successful in earlier wars, was forced to swallow a string of losses in the first years of the War of the Spanish Succession.

In the summer and autumn of 1702, John Churchill (1650-1722), the Earl of Marlborough, led a combined Anglo-Dutch army into Flanders in his first major campaign as sole commanding general. He captured Liège and several other towns. These victories and his wife’s influence — Sarah Churchill was Queen Anne’s chief lady-in-waiting and closest confidante — secured the elevation of Churchill’s earldom to a dukedom at the end of the year, and, more importantly, he was appointed Captain-General of the Army, ie. de facto commander in chief of all British land forces for most of the rest of the decade.

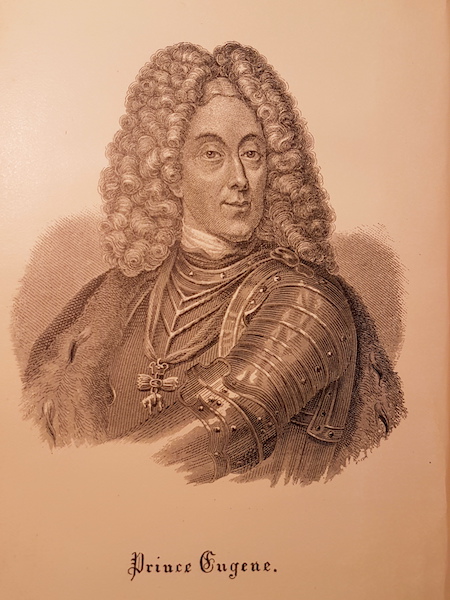

At the same time, Prince Eugene of Savoy, the other great Allied commander, was mopping up northern Italy. He was a member of the junior branch of the house of Savoy, which was fighting on the other side. He had been raised in France and had hoped in his youth to serve Louis XIV, but the Sun King took against him for some reason, allegedly because of a scandal involving his mother, but perhaps also because Eugene was obviously so much more gifted than his own son. Eugene consequently offered his services to the Emperor Leopold, who gladly accepted them.

Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736).

Eugene’s cousin the Duke of Savoy made a surprise move in 1703, switching sides to join the Grand Alliance, thus betraying his cousin, Louis XIV (the Duke’s grandmother had been a sister of Louis XIII), and his son-in-law, Felipe V. He gained little by this move, which drew Eugene’s army into Savoy. The year saw no conclusive battles, however, on the Italian front or any other.

Louis XIV became determined to strike a decisive blow in 1704. He marshalled his vast resources and expanded his forces to some 450,000 men by the spring of that year. Against the advice of his own Minister of War, he resolved to strike at the enemy’s heart. Dispatching the smaller part of the army to keep Marlborough busy in Flanders, he sent the greater part into southern Germany, where it was to link up with the Bavarian army and invade Austria, the objective being to capture Vienna, the Emperor Leopold’s capital. The French and Bavarians advanced so far and so quickly that the Emperor Leopold fled into Hungary.

Unfortunately for Louis, Marlborough was well aware of this plan, for there was an English spy at Versailles. Interestingly, his or her identity has never been discovered even though Louis soon guessed that there was traitor in his circle and presumably must have gone to some lengths to uncover him/her.

Cleverly evading his Dutch allies, who were determined to keep him Flanders, Marlborough marched his English army 400km to Bavaria, where he rendezvous-ed with the Imperials under Eugene and gave battle to the French under Maréchal Tallard at Blenheim on 13 August. It was a rout. At one blow, Marlborough destroyed Louis’ grand army and his hopes of an early end to the war. The grateful Queen Anne promised the Marlboroughs a grand country house, and Parliament voted a large sum towards its construction. We know it today as Blenheim Palace.

Blenheim Palace, Marlborough’s reward from a grateful queen and country. It remains in the possession of his descendants. Credit: Wikipedia.

1705 proved to be another inconclusive year on the battlefields. Eugene returned to northern Italy, where, under-resourced and outnumbered by the French under the Duc de Vendôme, his brilliance only served to maintain the status quo. Marlborough, too, found himself bogged down in Flanders again.

New Leadership

The most momentous developments of 1705 were off the battlefield. The elderly Emperor Leopold died mid-year and was succeeded by his eldest son, Joseph. The energetic new emperor effected a much-needed re-organization of the imperial finances and administration, which allowed Austria to prosecute the war with new vigour. The Emperor Joseph backed Eugene’s plans to engage the French in Savoy, where the French had been more successful than elsewhere. Eugene would eventually win a great battle against the French before Turin in the early autumn of 1706, driving them out of Savoy.

The Emperor Joseph when still King of the Romans, the title used by the Holy Roman Emperor’s heir. This miniature portrait in ivory is on display at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

More significantly still, Joseph decided to open a new theatre of war in Spain. Piggybacking on the revolt of the Catalans against Felipe V, he sent his younger brother the Archduke Charles to Catalonia in 1705 to launch his bid for the Spanish crown. Those who have read Parts I and II will remember that Carlos II’s will had named Charles as the reversionary heir in the event that the French princes declined the crown. The Austrians, in any case, took the view that the French claim was invalid. Charles met with such success in Catalonia, assisted by a successful assault on Barcelona in October, 1705, by an English fleet that had already taken Gibraltar, that he was able to enter Barcelona and be acclaimed king there by early 1706. By 25 June, the Anglo-Austrian forces were able to install Charles in Madrid as Carlos III.

Meanwhile, Marlborough scored another success against the French in Flanders. He met the Maréchal de Villeroi in battle near Namur, at Ramillies. It was the second of his great victories, and resulted in the conquest for the Grand Alliance of Antwerp, Bruges, and Ostend, effectively ending the French occupation of Flanders. When Villeroi returned to Versailles, Louis XIV remarked forlornly to him, “At our age, there is no more luck.”

Little did Louis know that matters would get worse still.

Please check back after Christmas for Part 5 of the series. Happy Holidays!

Leave a Comment