La Maréchale d’Aubemer, Nouvelle du XVIIIème Siècle, or The Widow of Field Marshal d’Aubemer: A Novella of the 18th Century, posthumously published in 1867, is a novel by the author and memoirist Madame de Boigne, born Adélaïde d’Osmond (1781-1866). Mine is the first English translation, available here for the first time anywhere.

In Chapter 1, the Maréchale d’Aubemer, a wealthy, worldly-wise widow of a certain age, weary of the social round, gives a ball and receives an unexpected letter.

THE WIDOW OF FIELD MARSHAL D’AUBEMER

CHAPTER ONE

The Pleasures of Being a Hostess

“My God, this noise is annoying!” said the Maréchale1 d’Aubemer rising out of the armchair in which she’d been reading, rather inattentively, the latest speech given at the Academy. She placed it on a gold-ornamented Boulle etagere, the various shelves of which were already filled with a history book, a new novel, several pamphlets, needlework, and a voluminous knitted vest.

“Who is making all this racket?” she asked one of the servants who answered her bell. “I’ve been deafened for an hour already.”

“It’s the workmen taking up the carpet of the big salon, Madame la Maréchale, and taking down the doors that open into the gallery.”

“Will they be finished soon?”

“I don’t think so, Madame la Maréchale, they’ve only just started.”

The Maréchale sank back into her armchair with an air of melancholy resignation.

“What an absurd notion of mine, giving balls! And for whom? And for what? Ah, this will be the very last one, I assure you.”

She took up her reading again, then put it down.

“Still,” she said to herself, “let’s go see what these workmen are up to, just to head off any stupidity. If I’m going to give this silly ball, it ought at least to be arranged as it should be.”

The workmen were not committing any stupidities. They were taking the furniture out of the rooms, hanging the replenished chandeliers, placing the stands for the orchestra and the flowers, and setting up the tables for the buffets and the supper.

Everything was being prepared according to the usual pattern of the parties frequently thrown by the Maréchale for some years past. There was nothing to find fault with. She returned listlessly to the salon that she was accustomed to inhabit in the morning. It was in no way subject to the upheavals being imposed on its more magnificent and less comfortable neighbours. Seated on a small chair in front of the fire, elbows on her knees and her head in her hands, Madame d’Aubemer was immobilized in deep thought. The result of her meditations was to call her major-domo and to give him numerous instructions on how to distribute the refreshments. At the last ball, there had been some crowding; she thought to resolve the problem by installing a second buffet at the far end of the rooms. Monsieur David raised objections. How would the servants get there? It had never been done this way! The Maréchale, sufficiently irritated by these objections to forget to take her wrap, energetically walked M David into the salons and showed him how by making use of some back stairs nothing would be easier. M David was forced to agree, but Madame la Maréchale would have to explain it herself to Mademoiselle Julie, who didn’t let anyone use those stairs. They led to her room, and she had no intention of letting anyone dirty them. The Maréchale opened the door to the stairs, saw that they were well waxed and covered by a runner, raised her shoulders slightly, and said, “It makes no matter, David, I want a buffet there, serviced by these stairs.”

“It shall be done, Madame la Maréchale.” David went away muttering to himself that Madame’s notions were getting stranger by the day.

Madame d’Aubemer, chilled while crossing these large rooms of which the windows had been opened to let out the dust, felt quite uncomfortable. Wrapping herself in her shawl, she was just taking up her reading again when a tray a letters came to interrupt her. “Still more!” she cried, casting a look of distress at her writing table, already covered with letters. All of them, in more or less familiar, more or less demanding terms, and in the name of the most touching sentiments, requested invitations to the ball for charming dancers whose taste for good company had to be encouraged; for artless maidens first coming out; for accomplished young women whose brightness would add lustre to the party; even for old parents who didn’t go out much, but who had a lively desire to see once more all that was most brilliant in society, etc., etc. The new notes were of much the same kind; answers were being waited for2. The Maréchale gave a few affirmative ones to spare herself the bother of writing, not without thinking of how many difficulties it would make for her with regard to those she had previously refused. Drawing resolve from her ill-humour, she said in response to others, “I’m out, and if they come back, I haven’t come back; see that the door is closed.” She then took up the unfortunate speech that she had started reading with such interest, but which suffered from all these multiple distractions. Yet she wanted to discuss it with the author, and was nonchalantly turning the pages looking for some striking sentence that she could quote to him when the Duchesse de Montford was announced.

“Dear friend, I know you are not at home. I know you’re not giving any more invitations to your ball tomorrow; consequently, I’m coming in, and I’m taking two,” she said while moving towards the table where there was a pile of invitations; helping herself to two of them, she said “You’re going to ask me for whom? I know nothing about it.”

The Maréchale smiled. “I like it better that way. My conscience will be more at ease with regard to those I’ve told very truthfully that giving them an invitation is impossible. Only explain to me why it’s so important to you that you would go to such lengths for people unknown to you?”

“Truthfully, it’s not important to me at all, but I could not do otherwise. Henri d’Estouteville has ordered me to carry off these invitations, and what he wants done always gets done, I don’t know how.”

A light shadow of friendly irony slipped across the Maréchale’s face.

Comte Henri d’Estouteville was incontestably the most fashionable man in all of France, and, for the moment, the very attached lover of the Princesse Simon de Montford, the duchess’s daughter-in-law. Before him, the holders of this post, frequently rotated, had got nothing but disdain and sarcasm from the duchess, but M d’Estouteville had put such skill and winning manners into his conduct that he reigned despotically over the Hôtel4 de Montford. He kept Princesse Simon to more respectful dealings with her mother-in-law and a more agreeable attitude towards the world. As for Prince3 Simon, it was hard to guess if he was aware of his wife’s conduct, and still less if he took the least interest in it.

“Why then didn’t you send me that irresistible Estouteville in person?”

“Because he said you were not at home, ill, annoyed, recalcitrant, what have you. That only I would succeed in seducing you or browbeating you. In the end he concluded that I should come, and here I am. He was right, since I’m taking the two invitations away.”

“You know whom they’re for?”

“No, but certainly for very presentable people.”

“If you suffocate at this damned ball, it won’t be my fault, remember that! Despite all this sulkiness about which M d’Estouteville surely made up a very diverting tale, my hand was forced from all sides.”

“Oh, look at you grumbling! Ha! It’s ugly and it doesn’t become you at all. You don’t know how to carry it off. Rest easy, my dear, your ball will be charming, and the next day’s compliments will make you forget all the annoyances of the day before; you’ve always been this way.”

“It is a little bit true,” replied the Maréchale under her breath, but then added in full voice, “Every time the weariness of the day before is greater, the fatigue of the day is more tiresome, and the success of the day after leaves me more indifferent; it’s just as well that this is the last ball I shall give in my life.”

“Come now, that’s a remark of the day before. Your balls are the most charming in Paris. All the young set will ask for more of them, and you won’t refuse them.”

The Maréchale shook her head with a melancholy air. The noise of hammering coming from nearby just at that moment, she exclaimed, “Do you hear that hideous racket? That’s one of the pleasures of throwing a party!”

Madame de Montford began to laugh. “My dear Maréchale, you have some spleen5. You’re not such a spoiled child that you would allow yourself to be so put out by a few forcefully extracted invitations and the sound of a few necessary hammer blows if you were yourself. Come now, calm yourself. What are you reading there? M ——’s speech. Ah, your handiwork!”

“What, the speech?”

“No, the academician.”

“How can you say such a silly thing? And you, who are supposed to be my friend, how could attribute such an absurdity to me?”

“I, your friend, don’t want you to be so easy to irritate. Where’s the harm if the interest of a person as distinguished as yourself turns to the profit of the people in whom she takes such a lively interest? You are being quite unreasonable today. I cannot let this bitter outlook on an existence as pleasant and liberated as yours pass.”

“Oh, yes! Very liberated, to be sure.”

“So brilliant, so envied. Really, what do you have to complain of? You’re really going to be peevish? Do you not have, by everyone’s admission, the most agreeable house in Paris, the only one where there’s any conversation?”

“I do in fact have the honour of listening to the most boring person in the room while the wits chat amongst themselves a few feet away from me. That’s the reward of a skillful hostess.”

“So dine out on the distinction that is so much sought after everywhere.”

“I’m too old. The years weigh heavily on me.”

“But I’m your elder, and I wear mine very lightly.”

“Oh, it’s different for you. You have ambitions for your husband, duties at court, children…”

“And a daughter-in-law, no?”

“But that also has a certain interest in it. I have nothing to occupy myself but myself, and it’s this enforced egoism, which you call liberty, that’s unbearable to me. It makes me feel disgusted with this Maréchale d’Aubemer of whom I must think exclusively.”

“To that, my poor friend, I have nothing to say. You are, in fact, very isolated, but could you not find a bit more company?”

“One doesn’t willingly enter into artificial relations. I’ve tried, but nothing worked. I attached myself to that poor Chevalier d’Aubemer6, I made up fantasies about him, I wanted to to adopt him, I wanted to get him married, and you know how that faithful boy perished. That was my last illusion, and my last hope!”

“But you have your sister, a widow like yourself. Why don’t you make it up with her?”

“Caroline has been buried in the mountains for twenty-five years. We wouldn’t have anything in common, we would be mutually insufferable, and then, she adores her daughter.”

“Come, come! Here you are, after envying me my children, finding fault with your sister for loving hers! But this niece…I seem to remember she was a good girl.”

“Oh, please spare me. A hussy who refused the poor Chevalier d’Aubemer in order to marry her cousin, that good-looking boy you saw at my house last year, I think. It didn’t take me even half an hour to see that he was bad news.”

“You are decidedly out of sorts. I will go back to my first observation, you are splenetic, my dear. I’ll trust in your evening regulars to distract you and get you out of it.”

“My evening regulars! Do you think I could stay here in such a din? And I don’t dare go anywhere for fear of meeting people who will make grimaces at me or ask for invitations for tomorrow.”

“Come to my box at the Comédie-Italienne7. The young ladies are making up a party among themselves. I’ll be there alone and we shall barricade ourselves.”

This last bit of dialogue took place by the door through which the duchess was going to leave. It opened and a servant presented a tray with a single letter. The Maréchale recoiled.

“I’m not here, I don’t want it!”

“In truth,” laughed Madame de Montford, “you have letterophobia, dear friend. Now make up your mind. Are you coming to the Italians?”

“What’s on tonight?”

While the ladies were discussing how to spend their evening, Madame d’Aubemer, with that idle curiosity that leads one to examine letters as if they were enigmas when one should just open them right away, was inspecting the stamp of the one she was holding in her hand. With a quick movement, she drew near the window while removing the letter from the envelope and cast a keen eye on the opening lines.

“It’s my sister’s hand,” she said, “I didn’t recognize it in the address, but the Uzerche8 stamp alerted me. Here, Madame de Montford, listen to this first sentence and tell me if I’m right to say that my sister and I no longer have anything in common: ‘I know my dear Émilie’s heart too well to think that the world could have succeeded in corrupting or even altering it…’ The world9 corrupting the heart? Could there be a more provincial notion? In truth, this poor world, slandered by the common herd, has no fault other than that of being profoundly dull.”

“As for that, I agree with you entirely, and so as not to start nagging you again, I will fly. And I hope to see you tonight at the theatre.”

“I’m not sure.”

“Oh, come!”

“We’ll see.”

Madame d’Aubemer turned back to the window to finish reading the letter, but the light was fading, so she put in on the mantle, sat down on her little chair in front of the fire and began to poke at it. “That poor Caroline,” she said to herself after a long and hazy bout of musing, “the world is certainly what I have loved the most these long years.” The memories of youth which had produced this reflection having lead her to the desire to read what her sister had sent her, she rang and asked for some lights10. While they were being prepared, M David came to inform her that the workmen had finished; were there further orders to give them?

“Are the windows closed, David?”

“Yes, Madame la Maréchale.”

“My wrap, my hood; there, that’s good.”

Her precautions taken this time, Madame d’Aubemer carefully inspected all the arrangements she ordered, made sure that the buffets were set where she had indicated, gave detailed instructions for the next day’s food and drink service, and returned to her armchair to find a good fire with keen pleasure, and the letter with a good deal less tenderness than she had felt at the moment that M David had interrupted her.

I know my dear Émilie’s heart too well to think that the world could have succeeded in corrupting or even altering it. It is therefore with complete confidence that I appeal to it.

My daughter is going to Paris with her husband. I commend her to you, sister, not to take her to the opera and to balls, but to watch over her maternally. You see to what degree I am counting on your goodness and that tender love that prevailed between us for too long ever to be effaced.

I am confiding to you not only what I hold most dear, but the most sacred thing there is, a young woman who has never known grief and does not even know that it could befall her.

Dear sister, protect her in a world in which she is going to be so much a stranger and perhaps so strange. I have to trust in the hope of your solicitude to muster the courage to watch my child leave.

Good day, dear Émilie, Caroline presses you tenderly to a heart whose anxiety and bitterness it is up to you to assuage by accepting her request.

“Another nuisance!” thought the Maréchale. “It will just suit me to take a little country girl around, applying herself only to using me to gain entry where doors are closed and to get tickets for precisely those performances for which none are left! Still, I shall be happy if that’s all. She will perhaps hang off my neck, calling me “Aunt Émilie,” or “Madame la Maréchale” at every turn, according to whether she’s playing the Grace or the Muse of Uzerche, depending on whether she’s trying to be artless or grand. I shall be perfectly happy! I compliment her on having the good fortune to be the wife of the Count Lionel de Saveuse. That gives me the measure of her. After all, she knows no better, and there are people who find him quite handsome. On that note, is there anything in the letter about the girl’s looks…no, nothing. She’s surely ugly at the least. Or perhaps hideous…no, not hideous, or her mother would have added a few words to prepare one for the shock. Quite ordinary looks, then. Yet Caroline is right. The happiness of a young heart is something sacred, but how does she think I can be the guarantor of it? Alas, is happiness not founded on illusions, and who has ever preserved them? Well, I shall do my best. But what a heavy burden has fallen into my arms. I don’t want to think about it any more. To each day its sufficiency of pains.” And so Madame d’Aubemer resolutely took up her much-interrupted reading again, turning the pages without paying the least attention to them.

“I shan’t dress until after dinner,” she said to Mademoiselle Julie who appeared at the door to announce that the hour for that meal had passed. She didn’t sit down at table, but ordered some broth of which she ate a few spoonfuls, and leaned back in her armchair. Her strained vision did not permit her to read for very long in the dim light. Resorting to the knitting that was awaiting her on the table, she sank deeper and deeper into melancholy reflection. Before nine o’clock she passed into her bedroom and rang for her women.

“I’m not going out. I’m going to take advantage of my not being at home to go to bed. I have a headache and my throat is decidedly scratchy.”

“That’s not surprising given the way Madame is turning the house upside down,” replied Mademoiselle Julie angrily.

Madame d’Aubemer saw that David had not kept the secret of the back stairs. Since the cat was out of the bag, she saw no point in talking about it and held her peace, in which Mlle Julie imitated her with a glowering air. The order was given not to mention Madame’s indisposition for fear that any rumour of it, getting out, might cast doubt on the next evening’s party if it reached the ears of the fashionable set, people who knew their importance, wanted to be asked everywhere, frequently bestowed their presence and always their criticism, but could be put off by the least difficulty. Her elevated social position notwithstanding, the Maréchale set store by having them at her ball.

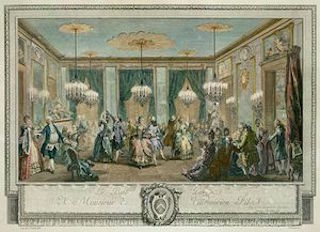

Madame d’Aubemer had a bad night, a sore throat having been added to a violent headache by morning. The same scruple that had dictated the silence of the previous day prevented the summoning of her doctor. She stayed in bed, attended to by her servants, each one sulkier than the last. Finally, with the help of orange blossom water, ether, and above all a strong will, she pulled herself together into a state fit to get up, attired herself simply, yet richly and nobly, and towards ten o’clock entered her splendidly illuminated salons. She had been preceded there by some mothers whose daughters were homely or of small fortune, and who had wanted to stake out good spots for them, knowing full well that the male dancers would not come to seek them out in the crowd.

The Maréchale cast a practised eye around the rooms, and, seeing that nothing needed to be corrected, seemed to be absorbed in attending to a company about which she hardly cared and that was not at all made of the stuff she cared for most. Soon the truly smart people arrived and the party got underway.

After having said quite sincerely to the Duchesse de Montford, who was leaving around midnight, “You are lucky to be going. I would like to do the same,” the Maréchale spared no effort to prolong the ball. The news, skillfully put about, that a supper à la polonaise11 was to be served at six o’clock retained a lot of people. Novelty always seduces in Paris; people wanted to be able to talk about the supper à la polonaise the next day. It was very good, very choice, as indeed had been the party. Everything had come off with complete success, and Madame d’Aubemer was entirely satisfied. A eight in the morning, she returned to her bedroom extenuated by fatigue. She was almost unconscious as her women undressed her. There was no further obstacle to summoning her doctor. He found her in the grip of a strong fever; by evening, she was dangerously ill.

- Maréchale is a courtesy title accorded to the wife or widow of a field marshal. There is no English equivalent, but opera fans will recognize the German form: Marschallin, as per the heroine of Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier. In this book, the Maréchale is also sometimes called simply Madame. The respectful form of address is “Madame la Maréchale.” In general, the French forms of all titles and forms of address will be used here. In most cases, the spelling is similar enough to English for the reader to guess the equivalent title. Dissimilar titles, or ones that do not exist in English, will be footnoted as needed. See #6 below as an example.

- Footmen waiting to take the replies back.

- Some very old and grand French ducal houses used the courtesy title “Prince” for the heir to the dukedom. The title had no legal basis in the Ancien Régime peerage. See also the duke and prince de Guermantes in Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past.

- A large private townhouse, not a hotel in the English sense.

- The English word was used in the original.

- A kinsman of her late husband, of whom more will be learned in Chapter 2. Chévalier is the French title for the holder of a knighthood.

- There were 2 main theatre companies in Paris before the Revolution: the Comédie-Française and the Comédie-Italienne. The former still survives, the latter does not. People spoke of going “to the French” or “to the Italians,” as will be seen.

- A small town in the mountains of south-central France, the Massif central, south of Limoges.

- The social world of high society and the court.

- Candles.

- In the Polish manner. Since the consort of Louis XV was a Polish princess, there was a minor vogue for things Polish.

I’m definitely ready for more! Surely the author isn’t going to kill off the title character in the second chapter. I would be interested to know what the supper in the Polish style would comprise.

Have no fear. The Maréchale will live to fight another day, so to speak! As for the Polish supper, yes, I must look into that. Thanks for commenting!