La Maréchale d’Aubemer, Nouvelle du XVIIIème Siècle, or The Widow of Field Marshal d’Aubemer: A Novella of the 18th Century, posthumously published in 1867, is a novel by the author and memoirist Madame de Boigne, born Adélaïde d’Osmond (1781-1866). Mine is the first English translation, available here for the first time anywhere.

In Chapter 2, we go back in time to learn how the Maréchale d’Aubemer and her sister became estranged.

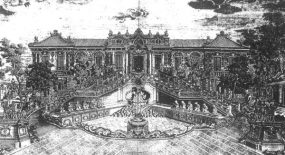

La Maréchale d’Aubemer

Chapter 2

A Retrospective Chapter

It’s no doubt tedious to go backwards, but the writer and the reader must have the fortitude to bear a few retrospective pages in order to explain and understand Mme d’Aubemer’s past, which is already rather a long one for the heroine of a novel. For we do not wish to take anyone by surprise, and we admit, at the risk of the reader throwing these pages aside with disdain, that the Maréchale is indeed the object of our attentions.

Her father, the Baron d’Élancourt, a widower retired from military service, lived on his lands far away from the capital. He believed he had committed an act of high wisdom in appointing a man of business, whose integrity he never doubted, as guardian of his two daughters. Charging Monsieur Duparc with the administration of their fortune and the settling of their futures, he stipulated that they should remain at their convent1 until the day of their marriage. The Mesdemoiselles2 d’Élancourt had been orphaned for five years and the elder had reached the nineteenth year of her age when M Duparc presented a Monsieur Dermonville to her as a suitor. The boredom of life in the convent brooked no hesitation, and she accepted her guardian’s offer with satisfaction. A few weeks later she married M Dermonville, to the great dissatisfaction of her family, who had not been consulted. The public in general decried this marriage. It was thought that Mlle d’Élancourt, a young woman of quality, allied to the greatest houses of France, having thirty thousand livres in income, and being quite a remarkable beauty, should not have married a 45-year-old man whose only distinction was a large fortune. One could have added good sense and a happy disposition, but these are the sort of advantages that count for little in the world, and the rumour spread that M Duparc had sold the charming young Émilie d’Élancourt to the highest bidder. M Dermonville enveloped his wife in great luxury, setting up her household on a very elegant footing, and she became an arbiter of fashion, the kind of importance which is absorbing at the beginning of life and leaves no time for regrets to take shape. Émilie therefore seemed quite satisfied in the bonds of a union so disproportionate in age and birth.