La Maréchale d’Aubemer, Nouvelle du XVIIIème Siècle, or The Widow of Field Marshal d’Aubemer: A Novella of the 18th Century, posthumously published in 1867, is a novel by the author and memoirist Madame de Boigne, born Adélaïde d’Osmond (1781-1866). Mine is the first English translation, available here for the first time anywhere.

In Chapter 11, Gudule sits beside an old soldier at dinner. He has much to say about his adored young colonel…

THE WIDOW OF FIELD MARSHALL D’AUBEMER: A NOVELLA OF THE 18TH CENTURY

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Secret Progress

Country air, exercise, and a manner of living closer to her own habits restored Mme de Saveuse’s health. She had recovered her bloom, and sometimes her gaiety, but not the serene equanimity of her temperament; she had frequent relapses into sadness. Lionel was more than ever under the thumb of the Princesse de Montford, who could not have ruled him more painfully. For two years she herself had submitted to the yoke, having been dominated by Henri; she compensated by exercising an absolute and capricious tyranny over M de Saveuse. The fact that Princesse Simon’s name came up incessantly in Lionel’s conversation forced Gudule to think about the sorrows that she considered her to have caused her, never without astonishment that such a woman could inspire tender feelings. This thought came to her first with regard to Lionel, but quickly passed over him to settle for a long time on Henri, whose superiority she made no bones about acknowledging. These purely philosophical reflections did not alarm her, but captivated her mind, and filled her leisure, so much so that she was constantly occupied in seeking to explain M d’Estouteville’s passion for Mme de Montford. And yet it was the only thing she did not talk about to Mme d’Aubemer, who, for her part, did her best to hide Lionel’s conduct, and gave her the niece the greatest proof of her affection in sparing no effort to keep this husband, who was becoming more and more insufferable to her, at Magnanville. One morning when the two ladies were working side by side, lost in their thoughts, the Maréchale broke the silence by asking Mme de Saveuse when her love for Lionel had begun.

“In truth, Aunt, I don’t really know. I was always taught to consider him my future husband.”

“But, after all, you must have had a pressing reason to refuse the poor Chevalier d’Aubermer with such a high hand.”

“As to that, I can answer more clearly. I wanted to stay at Saveuse with my grandfather, and never leave Mama.”

Mme d’Aubemer raised her eyes and looked at her without speaking. Gudule blushed a little.

“It’s true, Aunt. But that wasn’t to be presumed. And now I’m told it’s my duty.”

She turned her head to hide a few furtive tears, and the Maréchale, sorry to have provoked them, hastened to change the subject.

The summer passed on. D’Estouteville wrote very witty letters to the Maréchale from further and further away. She showed them to her little circle of intimates, which was an occasion for them to praise him.

Lionel’s liaison with the Princesse de Montford began to be noticed in society, to the great satisfaction of the one and the perfect indifference of the other. The Duchesse de Montford, on the other hand, was very angry about it, and Prince Simon was annoyed. Lionel bored him and was of no possible use to him, while Henri talked so well and had good connections that could be useful in case of need. Otherwise, he continued to turn his customary blind eye, having only warned his wife that he found her M de Saveuse a crashing bore and did not wish to be exposed to the danger of encountering him during the few brief hours that he was not in his study. Poor Lionel, meanwhile, knowing that in theory he should befriend the husband, made a thousand overtures of the most awkward kind, and Prince Simon feared that he would not be able to hold back a rebuff the effect of which would undo the whole line of conduct that he had found it convenient to adopt.

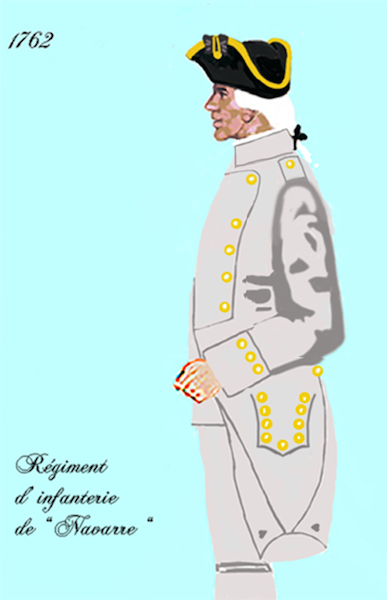

Since time immemorial it had been the custom for the curé1 of Magnanville to dine at the chateau on Sundays. Though it was the last one of the season, he nonetheless excused himself. His brother, a lieutenant in the infantry who was recovering from an illness, had just arrived at the presbytery. The Maréchale sent to tell him to bring his brother. Despite the curé’s encouragement, his brother felt quite embarrassed in such brilliant company and seemed very ill at ease. Gudule, with her good manners and good heart, took him under her special protection. She had him seated next to her at table, and first spoke to him of his brother, then of his native countryside, which he had not visited for twenty years, and then finally of his regiment. There she had found the topic that gladdened the old lieutenant’s heart. He expressed himself with all the love that he bore his regiment, which led directly to its colonel, the object of his passionate enthusiasm. This colonel had made his debut as a sub-lieutenant in his own company. He was at that time the most lovable and waggish youngster, and had the best heart. The lieutenant smiled thinking of it. He himself had trained him in his military duties, and he dared to say that he was deficient in none of them, but then he had lost sight of him for a time. The Countess could imagine with what joy he had seen him arrive the year before as colonel2 of the regiment! Not having forgotten him, the Colonel called him his good maître ès armes3, thanked him for his former severity (which he was right to do, for it had cost him a great deal), and loaded him with marks of his regard. In any case, his solicitude extended over the whole officer corps as well as over the soldiery. He was adored for it, and all would give their lives for him. Come the war, one would see what Navarre4 could do under such a chief! Then followed a multitude of verbose details in support of the colonel’s talents, merits, and virtues, and finally a recitation of the almost filial attentions he had received from him during his recent illness. Here the lieutenant became tenderly affected and paused for a moment. Gudule waited with great interest and a slight palpitation in her heart. He resumed, saying “All the same, I hope that the colonel isn’t taking a distaste to the service. We’re finding him rather gloomy this year, and when I told him I would be spending my sick leave with my brother, the curé of Magnanville, imagine it, Madame, he sighed as if his heart was going to break, and replied ‘You are very fortunate.’ My word, if Count Henri d’Estouteville is not the most fortunate of young men, I don’t know who is!”

Mme de Saveuse had been expecting that name; a secret instinct had augured it. She was not surprised, yet she blushed excessively. Dinner ended together with the lieutenant’s remarks. Gudule recalled them wistfully when she retired to her rooms in the evening; she was touched by the officer’s good nature. Then she thought with less satisfaction that that sigh, sorrowful enough to strike even an old soldier’s blunt nature, had been breathed for the Princesse Simon. Placing her head on her pillow, she could not stop herself from wishing that some attachment more worthy of M d’Estouteville would tear him away from this sinful liaison. She would have liked to see him marry a woman capable of appreciating so many good qualities and of leading him down a path other than the one he was walking on. Gudule fell asleep with these thoughts in her mind and dreamed that she herself was this woman. She had not forgotten this ridiculous dream the next day, but she smiled at it without being troubled by it.

Notes:

- A curé is the equivalent of a vicar in the Church of England; in other words, the parish priest.

- Under the Old Regime, nearly all officers were aristocrats and their commissions were purchased for them by their families. Very young men found themselves captains, majors, and colonels after a short time in training as described here. Youthful princes were even given nominal command over entire armies. The prudent ones allowed themselves to be guided by experienced subordinates such as this old soldier.

- Literally master at arms, i.e. the master under whom he had trained.

- Navarre, formerly a kingdom that spanned the Pyrenees on the Atlantic side of the Iberian peninsula, had been brought partly into France by the accession of its last king to the French throne as Henri IV in 1589. This regiment is apparently Navarrese; presumably the lieutenant is, too.

Leave a Comment