While browsing in my local antiquarian and secondhand bookshop, Condor Fine Books, I happened on a nearly 40-year-old volume entitled Land of the Firebird: The Beauty of Old Russia, by Suzanne Massie.

Land of the Firebird: The Beauty of Old Russia, by Suzanne Massie.

Leafing through it, I was delighted to find that an entire chapter was devoted to one my favourite Versailles Century (1682-1789) characters: Elizabeth Petrovna, Empress and Autocrat of All the Russias. An able ruler, she was also a great beauty and a woman of prodigious appetites.

Portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna by Vigilius Eriksen (1757). Credit: Wikipedia.

As I’ve stated before, the fun-loving yet religious Elizabeth has in my view been unfairly overshadowed by her more rational and intellectual protégée, Catherine II the Great. Imagine my pleasure when in the very first paragraph of the chapter on Elizabeth, which is titled ‘Elizabeth: Bright Colors and Gilt’, Massie writes of the 4 empresses who ruled Russia between Peter the Great’s death in 1725 and the end of the 18th century that “Two of them were exceptional: Peter’s daughter, Elizabeth, and a little princess from Germany who came to be called Catherine the Great. In the fifty-five years of their combined reigns, these two women, totally opposite in taste and temperament, were both in their different ways to lay the foundations for the flowering of Russian culture that was to come in the 19th century.”

The beginning of the chapter on Elizabeth in Land of the Firebird.

Writings about Elizabeth are scarce in English, also in French. The fact that Massie devotes nearly 20 pages to Elizabeth, and that she gives Peter the Great’s daughter her due, convinced me to buy the book just for this one chapter.

Focusing on the cultural aspects of Elizabeth’s 20 year reign (1741-1761), Massie makes some salient points that I hadn’t considered before. For instance, although the great imperial residences of St. Petersburg and its environs, namely the Winter Palace, the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoye Selo, and Peterhof, took their present form in Elizabeth’s reign, the last-named was the only one she had significant time to enjoy. It was finished in the late 1740s, but the other two were only completed late in Elizabeth’s life. She in fact spent most of her years on the throne living in temporary wooden palaces. The greatest of these was the Summer Palace on the banks of the Neva, which Elizabeth’s grandnephew, the Emperor Paul, had dismantled to make way for his brooding, fortress-like Mikhailovsky Palace. Given the Empress’s fondness for hunting, excursions, and pilgrimages, the court also tended to spend considerable time in the summer months living in lavish tents.

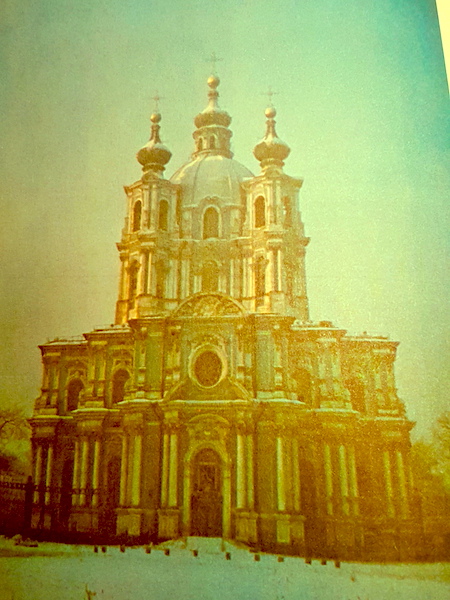

Rastrelli, the Italian architect Elizabeth commissioned for the new palaces, also designed one of St. Petersburg’s most beautiful churches, the Smolny Cathedral, which can be seen in the picture below. Massie asserts that here Rastrelli and Elizabeth conjured something completely new. First, Elizabeth enjoined Rastrelli to study old Russian churches in Moscow. She didn’t want a replica, however. She wanted a traditional Orthodox floor plan filled with Rococo light and gold. In Massie’s words, “assimilating Elizabeth’s new ideas with his own genius, he succeeded in creating something new for the Russian 18th century which can be called Elizabethan Rococo…”

Illustration of the Smolny Cathedral in Land of the Firebird.

Another aspect of Elizabeth’s reign that Massie helpfully highlights is her patronage of the arts, both visual and performing. Massie writes: “The age of Elizabeth was a time of bright colors and gilt, of gaiety and extravagance. Yet Elizabeth’s constant demands for parties and entertainments were allied to a real love for music, painting and the theatre. From her magnificent caprices, her generosity and enthusiasm for the performing arts, Russian opera, ballet and theatre were born.” The first Russian-language opera, by one Volkov, premiered midway through Elizabeth’s reign in 1751.

The Empress was famously extravagant. It was said that 15,000 dresses were found in her wardrobes after her death, and that her Paris milliner had refused to extend her any further credit. She also loved jewels, and it was to take advantage of her enthusiastic patronage that Western jewelers began to seek their fortunes in St. Petersburg and Moscow, thus starting a trend that would continue right down to the end of imperial Russia — think of Fabergé. Elizabeth herself was often covered in precious stones, the more colourful the better. As Massie puts it, “It was the heyday of the colored gemstone in the bright Russian hues that Elizabeth loved — red rubies, green emeralds, deep-blue sapphires combined with diamonds. The Russian love of nature and flowers that had brightened the walls of the Kremlin palaces and churches now blossomed into sparkling gems to adorn white shoulders and glistening curls. Instead of real flowers, bouquets of many precious tones, each different in color, shape and character, were worn on the bodices of gleaming silk dresses.” See below for some specimens.

Elizabethan jewelry (left) and views of the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoye Selo (right) in Land of the Firebird.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this visit to Elizabethan times in Old Russia. I certainly have. I’m beginning to think that it’s high time for Versailles Century to pay a visit to St. Petersburg?

Did you know that Versailles Century has both a Facebook page and a gallery on Instagram (@versailles_century)? Please ‘like’ and follow!

Leave a Comment