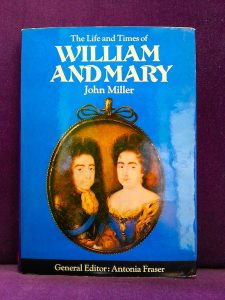

Small though it is, my local secondhand bookshop keeps turning up Versailles Century treasures. Yesterday it was this original edition of John Miller’s The The Life and Times of William and Mary, which was part of a ‘Life and Times of —–‘ series on British monarchs published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson. The series editor was the eminent biographer Antonia Fraser.

‘The Life and Times of William and Mary’ by John Miller.

This book, like the others in the series, is lavishly illustrated with both black and white and colour plates.

I’ve always been intrigued by William and Mary, who are such an anomaly in our history. They were the only joint sovereigns of the British isles, and among the few anywhere. That their reign was successful is due largely due to their harmonious marriage, and the fact that one generally deferred to the other, thus avoiding a power struggle. Mary, like any God-fearing woman of her time, believed it was her place to submit to her husband. William, for his part, who knew from the start that his wife was a potential heiress to the English, Scottish, and Irish crowns, once said that he would not be his “wife’s gentleman usher.” Even so, I had never really understood how the unprecedented joint sovereignty came about. The book explains it succinctly.

One faction of Parliament, keen to maintain as much legal continuity as possible in the wake of the ouster of Mary’s father, the deeply unpopular James II, wanted Mary to succeed on her own. An even more conservative faction wanted her merely to serve as regent and not ascend to the throne until her father’s natural death (overseas). A more radical faction wanted William to take the throne as sole monarch by right of conquest, for which there was a precedent in the case of William the Conqueror more than 600 years earlier. In the end, the compromise choice was joint sovereignty, with Mary’s sister Anne to be accepted as heiress presumptive. Thus the pair were crowned William III (r. 1688-1702) and Mary II (r.1688-1694).