Having grasped that Versailles, as the embodiment of elite French culture, was the key to understanding 18th century Europe, I soon realized that knowledge of the French language was indispensable. Not only was it the tongue of the most admired court in Europe, it was the lingua franca of the entire European elite from London to St. Petersburg.

French dictionary

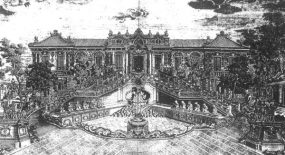

My new hero, Frederick the Great, for instance, spoke and wrote French in preference to German. Even when he spoke German, he is said to have spoken a Frenchified version of it. Legend has it that he once galloped up to a group of officers who were holding their troops back during battle and barked, “Messieurs! Warum attaquieren Sie nicht?” (“Gentlemen! Why are you not attacking?”). The point is that attaquieren is not a German verb, but one invented for the occasion from the French attaquer.

Frederick in the field

Furthermore, French was the language of the ‘Republic of Letters’, that group of what we would now call public intellectuals who lead the Enlightenment. Many of the most eminent of them were francophones, like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot, of course. However, even if the non-francophones published in their native languages, like, say, Hume in English, or Vico in Italian, they used French to correspond with their foreign peers. They also used French when they met in person, which was not often in those days before planes and trains, as did Frederick and Voltaire when the latter took up the former’s invitation to live — temporarily, as it turned out — in Potsdam. When Diderot went to St. Petersburg to meet his benefactress, Catherine the Great, they conversed in French. The Empress, however, was disconcerted at their first interview by the fact Diderot would thump her on the knee whenever he agreed with what she said. At their next meeting, he found that a table had been inserted between their chairs.

Catherine the Great

Continue reading