The Chapel was the last major component of the Château to be completed.

Louis XIV had been planning a grand new chapel in the late 1680s when the War of the League of Augsburg (1688-1697), also known as the Nine Years’ War, broke out. The plans for the Chapel were then shelved.

The Chapel of the Château de Versailles as seen from a street in the town.

When the planning resumed after the end of the war, the King had changed his mind about a crucial point of the design: instead of marble, the white stone known as banc royal would be used for the interior.

The effect, as you can see in the photo below, is stunning.

The interior of the Chapel of the Château de Versailles.

When work commenced in 1699, it was entrusted to Mansart, who was appointed Sûrintendant des Bâtiments (Superintendent of Buildings) in addition to his post as Premier Architecte (First Architect). He was assisted by his son-in-law, Robert de Cotte, who took over on Mansart’s death in 1708.

Not everyone approved. Despite her piety, the King’s secret wife, Mme de Maintenon, thought the project was a colossal waste of money — not because she begrudged the King a chapel, but because she believed that Versailles would be abandoned at his death, so the expense would be for nothing. And it was expensive. What’s more, the King insisted that the work should continue throughout the ruinous War of the Spanish Succession. (Please see my earlier series of posts on that war.)

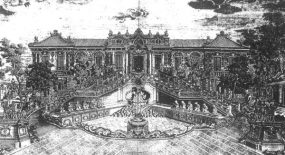

The exterior stonework and the inner shell were already complete by 1702. Some critics, then and later, objected to the fact that the Chapel’s roof breaks up the roofline of the Château. Saint-Simon, for instance, called it “a horrible excrescence.” You can judge for yourself in the picture below.

The Chapel of the Château de Versailles as seen from the courtyard.

It does indeed stand out above the roof of the Château. I rather like it, myself, as did one of the Château’s most perceptive historians, Ian Dunlop. In his magisterial book Versailles, he remarks on the almost medieval verticality of the Chapel’s design.

The Chapel, inside and out, was completed in 1710. Louis XIV heard Mass in it for the first time on 7 June. For the last 5 years of his reign, he made the daily promenade, called the Chemin du Roi, from his bedroom through the Council Chamber, the Hall of Mirrors, and the state rooms to the Chapel to attend Mass.

Whenever the King was present, the Chapel was of course packed. On the rare occasions that he was not, few people attended. Dunlop recounts an episode concerning ladies of the Court that was recorded by Saint-Simon. I think it’s worth quoting in full:

“They sat holding their candles so the the light fell on their faces and enabled them to be identified from the royal tribune. One day Brissac, major of the Guards, played a practical joke on them which was richly deserved; as soon as the ladies were assembled, he ordered the Guards to retire, saying that the King would not be coming. The Guards were turned back by their officers, who were in the secret, but not before the ladies — all but a few whose devotion was genuine — had withdrawn. Presently the King arrived, and was astonished at the smallness of the attendance. ‘At the conclusion of the prayers, Brissac related what he had done, not without dwelling on the piety of the Court ladies. The King, and all who accompanied him, laughed heartily. The story soon spread, and these ladies would have strangled Brissac if they had been able.'”

In the end, Mme de Maintenon’s fears were not justified. Although the Court did initially return to Paris during Louis XV’s minority, the Regent brought it back to the Château in 1722, not to leave again until the awful days of October, 1789…

I needed to thank you for this wonderful read!! I certainly loved every

bit of it. I have got you book marked to check out new things

you post…

Dear Chelsea

Thanks very much! It’s very encouraging to know that people out there are actually reading. Thanks also for bookmarking.

Best wishes,

David