La Maréchale d’Aubemer, Nouvelle du XVIIIème Siècle, or The Widow of Field Marshal d’Aubemer: A Novella of the 18th Century, posthumously published in 1867, is a novel by the author and memoirist Madame de Boigne, born Adélaïde d’Osmond (1781-1866). Mine is the first English translation, available here for the first time anywhere.

In Chapter 12, Henri meets with an accident…

THE WIDOW OF FIELD MARSHAL D’AUBEMER: A NOVELLA OF THE 18TH CENTURY

CHAPTER TWELVE

A Race Meeting at Vincennes

The end of the autumn saw M and Mme de Saveuse installed at the Hôtel d’Aubemer, and Lionel in the fulness of his glory, having manoeuvred his interests and pleasures to the fore. Gudule, having been presented at court by her aunt,1 had obtained a great success there, and everyone who anointed her that winter’s most brilliant star in the fashionable firmament attracted some of the hatred that the Princesse de Montford bore her. Princesse Simon nonetheless made conspicuous advances to Mme de Saveuse, which were rejected with a cold politeness that was attributed to jealousy over Lionel. The Maréchale was convinced of it and sought to distract her niece by surrounding her with attention and pleasures. She hoped to have succeeded up to a certain point, for Gudule once again adopted that serene gaiety and gentle equanimity that seemed to have abandoned her for a time. D’Estouteville, taking advantage of the new liaison so loudly publicized by Princesse Simon, had broken with her while at the same time keeping up appearances as expected of a well-bred gentleman; he still frequented the Duchesse de Montford’s salon, where he was perfectly polite to her daughter-in-law, but did not set foot in her house and no longer answered her letters. Lionel was very cast down by all this; well-versed in the sacred texts of gallantry, he knew that he should be full of regard for the supplanted lover now that he was no longer in the lists with him, but no more than Prince Simon did Henri give him the opportunity to put theory into practice, and he treated him with precisely the same familiar condescension as before his great success, not giving him any occasion to play the new role for which he had so diligently prepared.

Even before it had been quite noticed, Mme de Saveuse had divined the rupture between M d’Estouteville and the Princesse de Montford. She was very consciously pleased for him, and a bit more shamefacedly pleased to see a setback for the Princesse de Montford, whom it was her duty not to like. As for herself, she of course had no personal stake in the matter, and poor Gudule was even rather pleased with herself and the victory she had won over her own heart when she noticed in the course of the winter that her animadversion towards the Princesse had been allayed a good deal. There was no longer any question of returning to Limousin, and Comtesse Lionel, encouraged by her mother, resigned herself to her sojourn in Paris.

And Henri d’Estouteville, whom we saw so coolly laying plans for the seduction of Mme de Saveuse, had he renounced them after clearing away the initial obstacles? He had entirely forgotten them. Sincerely in love, he was preoccupied only with concealing his passion from the world, and from the Maréchale and Mme de Saveuse above all, for he had no doubt that he would be expelled from their society if he let it show. Sometimes he flattered himself that he had made some progress in Gudule’s heart, but he was too discerning to be truly vain on this score, and a cool word sufficed to discourage him. The open frankness with which Mme de Saveuse gave her agreement when she approved his words or actions disconcerted him; accustomed to the simpering and dissimulation of women rendered cunning by contact with fashionable society, he did not know that one can, without mistrusting the feeling, love a noble and pure soul with all one’s might. The honest Gudule, alas, was all the more unaware of it. In full security, she accepted the constant attentions with which Henri surrounded her without too much noticeable eagerness. Day by day the look of cold inquisitiveness, often so disdainful, that she had reserved for him at Magnanville began to soften. She no longer evinced surprise when she heard him express lofty thoughts or delicate sentiments, and her eyes resumed their habit of openly and frankly meeting his to seek that tacit communication that bore witness to the intellectual sympathy that existed between them. That was the only progress that Henri made during the winter, but it had cost him a lot of effort and he was happy for it.

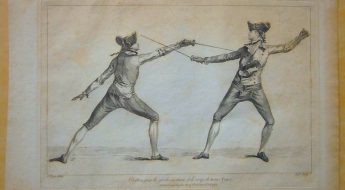

Such was still the situation when one fine spring day the announcement of a race meeting gathered all that was finest in town and court at the park of Vincennes.2 An accidental circumstance having pushed back the hour at which it was supposed to have begun, the young men wanted to alleviate the boredom of the wait by improvising a sort of steeple chase, and the carriages made their way towards the spot they had chosen. M de Saveuse had proposed this event in the morning, and showed himself to advantage. His handsome figure, invigorated by exercise and the elation of the success he and his horse had just won, shone in all its splendor, which made him the king of the race meeting. When d’Estouteville appeared, Lionel pressed him to join the racers in the next round, quite persuaded that he would conserve in the park the superiority that he was forced to cede in the drawing room. D’Estouteville accepted with the casual nonchalance that he brought to this sort of thing, and, giving his horse its head, he set off at a gallop. Presently he was seen to be heading back, taking the jumps with graceful suppleness. He had taken three of them, but at a moment when his horse, having grazed the last one, was running flat out, a child that had escaped its mother’s hand strayed into his path. D’Estouteville, fearing to trample the child, pulled back on the horse’s reins. It reared back and rolled over onto its master. A piercing scream was heard from Mme de Saveuse, who, standing upright in her aunt’s open carriage, would have fallen if M Chevreux, dragged to Vincennes by the ladies, had not received her in his arms; she had fainted. M Chevreux, more attentive to the principles of health than those of decorum, shouted to Mme d’Aubemer’s servants to open the carriage door, and before Mme d’Aubemer had time to countermand this order, Mme de Saveuse was stretched out on the grass a few steps from the race course, M Chevreux taking her pulse and assuring everyone that it was only a sudden shock that she would soon get over. D’Estouteville was not so grievously injured that he did not hear the scream, and, adroitly extricating himself from beneath his horse, he promptly joined the group gathered around the young woman, who was still unconscious. The Maréchale strove to recount how, in the carriage, they had thought the child was trampled, and how horrified Mme de Saveuse had been. Everyone greeted this version with a smile of incredulity, other than M Chevreux, who believed in it completely, and Henri, who did not dare to believe otherwise. Gudule, meanwhile, was regaining her senses, and opened her eyes. M Chevreux, in his naive simplicity, hastened to say to her, “Rest easy, Countess, the child was not harmed.”

“What child?” replied Gudule, and, her eye falling on Henri, she cried, “Oh, God be praised!” Then, hiding her suddenly reddened face in her hands, she broke into tears.

“This is the end of the nervous crisis,” said the imperturbable M Chevreux while the Maréchale bit her lips and Henri tried to hide the depth of his joy. Mme d’Aubemer, recovering first, attempted to direct the assembled company’s attention to the details of d’Estouteville’s fall in order to distract it from Gudule’s accident, but it suited the public’s malice too well to link the two facts to let them be separated, and already the names of M d’Estouteville and Mme de Saveuse were circulating in tandem.

Lionel, coming up behind, had raced to Henri’s aid, and, following his inclination, was occupied in getting the horse, more seriously injured than its master, back on its feet when Princesse Simon shouted to him, “Hurry up, M de Saveuse, your wife could not bear to see M d’Estouteville’s mishap without fainting of fright…perhaps she mistook him for you. Come reassure her by showing yourself,” she added, breaking out into a peal of laughter, and, taking hold of him, dragged him into the ever-growing group around Mme de Saveuse just at the moment that Gudule’s tears were bringing her back to life and to her senses.

Getting up calmly and with dignity, she pronounced herself fit to get back into the carriage despite the best efforts of M Chevreux, who recommended a few more minutes of absolute rest. The Maréchale hastened to precede her, but before resuming her seat in the carriage, Mme de Saveuse addressed her regards to M d’Estouteville, adding in the most matter of fact tone that it was the fright caused by his fall that had made her faint. Henri replied only with a deep bow and a look of reproach for attenuating his happiness in this manner. Gudule understood it only too well. She lowered her eyes and could not help raising them more tenderly; a flash of joy thanked her. A mutual correspondence of passionate love had just been established.

Mme d’Aubemer told her coachman to start. She would have thought it better to attend the real race, which was just about to begin, but the suggestion elicited such a painful “Oh, Aunt!” that she gave the order to return to Paris.3 Propped against the back of the carriage, the two ladies had no trouble following M Chevreux’s prescription to remain silent. As for the calm that he also recommended, neither one of them could pretend to feel it. Having arrived at the Hôtel d’Aubemer, M Chevreux insisted on taking Mme de Saveuse’s pulse again, found it to be very fast, and recommended that she be put to bed and kept there for the rest of the day. She felt too in need of solitude to resist. The Maréchale, for her part, foresaw vexations pressing in from every quarter and was not sorry to have some time to reflect at leisure, and M Chevreux was thus obeyed. However, before taking his leave, M Chevreux announced the project of going to see M d’Estouteville to persuade him to be bled.4 He had been struck by the alteration in M d’Estouteville’s appearance, opined he was more affected than he let on, and said that these falls that did not result in fractures were often the most fatal because of their after-effects. Leaving this new scorpion in Mme de Saveuse’s heart, the excellent M Chevreux withdrew, having in his naive simplicity turned the inner existence of his favourite pupil inside and out and compromised her in the eyes of society without having the least suspicion that he had done any such thing.

Hardly had the Maréchale’s carriage left when Henri had to admit that he was in a good deal of pain; his right shoulder was at the very least severely bruised and his wrist sprained. He had wanted to mount his groom’s horse since his own was injured, but recognized the impossibility of this course and accepted the Duchesse de Montford’s offer to take him back to his lodgings.

Lionel had been disagreeably impressed by his wife’s state. He knew that she was sensitive to the endangerment of others, but she had never in her life fainted; this displeased him. All the same, the care that needed to be taken of Henri’s horse, a superb animal, the excitement of the race course, the betting, the skill involved in fixing the odds, the attention given to regulating them, and the money to be lost or won, had all sufficiently distracted him that the episode of d’Estouteville’s fall had nearly been effaced in his mind when he dismounted at the Princesse Simon’s on his return from Vincennes.

“And so,” she said to him, “what position are you going to take?”

Lionel had been a thousand leagues5 from thinking that he would be called upon to make such a decision, but the Princesse de Montford acted so powerfully on this character that was as weak as it was coarse that within a quarter hour she had brought him to a excessive pitch of anger. Never, she assured him, had such a scandalous scene been played out in public, and Lionel would be the laughingstock of Paris if he did not testify to his resentment of it. Once alarmed over Gudule’s conduct, M de Saveuse, simultaneously forgetting his own actions and how much his diatribe would offend Princesse Simon, gave himself over to the most vulgar imprecations against women in general and his wife in particular; then, coming back to feelings that emanated more directly from himself, he lamented the downfall of such a superior being and reproached himself for having driven her to it. This phase of his regret was scarcely pleasing to Princesse Simon, and she interrupted him, saying in a mocking tone, “Well, then, there’s nothing for it but for the angel to be sent back to her paradise, since the Maréchale would perhaps be opposed to seeing her work out her salvation in a convent, and her influence would prevail over yours.”

Lionel placed his elbows on the table and remained for a few moments with his face buried in his hands; then, thumping violently on the table, he exclaimed, “No! It’s not possible! Gudule is frankness itself!”

“Oh, it’s assuredly not frankness that she lacked today: she very clearly told you and all Paris what her relations with Henri d’Estouteville are.”

Lionel began to stride up and down the room.

“Since you have no philosophy against a fairly common accident, though I judge it a rare scandal, you should not have exposed yourself to it. After all, it’s your own fault. Why did you not let her return to her old pile when she wanted to so badly?”

“I was told that I would look like a fool for letting the Maréchale’s inheritance slip through my fingers.”

“Who said that to you?”

“Henri d’Estouteville,” enunciated Lionel with a tremor of rage.

“Henri d’Estouteville! Oh, what a fine joke!”

And she threw herself back in her chair, overcome with laughter. Lionel stopped in front of her, his arms crossed: “Yes, very funny. He laughed like that.” He started pacing again, and the Princesse continued with her sarcasm.

“How that must have amused him, that you didn’t understand that he wanted you to keep her here in order to make her his mistress. How well they have played you!”

And as the Princesse de Montford’s hilarity continued, Lionel’s fury rose to greater and greater heights.

“And still, he has a shattered arm,” he muttered between his gritted teeth as he threw himself violently into a chair. Princesse Simon read his thoughts. Malicious as she was, she would not have worked to exasperate M de Saveuse to that end. She wanted to provoke a scandal, not a duel; she wanted to banish Gudule, whom she detested; she wanted to get rid of Lionel, who was beginning to be very tiresome to her; she wanted to get rid of both of them, and in so doing to take revenge on Henri, whom she still missed, by taking away from him the woman with whom she had known him to be in love for a long time, but who she was too experienced to believe was his mistress. She trusted in her own ability and in Lionel’s stupidity to calm the storm that she had whipped up once her goal had been attained. The Duchesse de Montford had taken d’Estouteville back to his lodgings and told her that his arm had swelled up abominably during the journey. Her daughter-in-law, whose plans were better served by this version, had concluded from this intelligence and affirmed to Lionel that the arm was shattered; by these means, though at ease as to the immediate consequences, she kept Lionel with her the entire evening and well into the night, relentlessly fueling his fury against Gudule, and assuring him that he must abstain from making an appearance anywhere until he had taken a position. Blockheads have certain ways of flummoxing even the most cunning; Lionel saw fit to say to her with a certain naivety, “And yet Prince Simon shows himself everywhere.”

The Princesse was speechless for a moment; then, restraining her anger, said coldly,”That is because he has taken a position.”

However, she promised at the same time to rid herself of such a blundering lover as soon as she could.

Notes:

- Any decently dressed member of the public could go to Versailles, wander about the public rooms of the chateau, and observe the ceremonies as a spectator. However, to take part in court life, one had to be presented by a sponsor who was already a courtier. This involved the sponsor formally presenting the aspirant to the King and Queen, or, if there was no queen at the time, to whichever princess was the first lady of the land.

- The Bois de Vincennes was a royal hunting preserve opened to the public by Louis XV (r.1715-1774). He laid out a number of avenues in the park, one of which is presumably the site of this race meeting. There is also a royal chateau, which is pictured. A proper hippodrome was built in the reign of Napoleon III, who made the park officially public.

- Today the largest park in Paris, Vincennes was still outside the city in the 18th century.

- Bleeding remained a common remedy for various ills until well into the 19th century.

- The league is an obsolete unit of distance equal to roughly four kilometres.

Leave a Comment