A Childhood at Versailles consists of the first 5 chapters of the memoirs of Mme de Boigne (1781-1866), née Adèle d’Osmond, who was a French salon hostess and writer. She was born in the Château de Versailles and lived at the court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette until her family fled to England during the Revolution. Later in her long life, she married a rich soldier of fortune 30 years her senior, hosted a brilliant salon in Paris, and became an intimate of the last French queen, Marie-Amélie, consort of King Louis Philippe (r. 1830-1848). Childless herself, Mme de Boigne addressed her memoirs to her grandnephew. The memoirs were not published until 1907, under the title Récits d’une tante, or An Aunt’s Tales. They’ve never been published in English, as far as I know, so I’ve decided to translate the first 5 chapters, the ones that take place mainly at Versailles, and post them here on this blog for interested readers to enjoy for free.

The chapters are quite lengthy, so I’ve broken each one into several parts. In Part 2.4, the author describes the court within the court of Louis XVI’s aunts, whose leader was Madame Adélaïde, the eldest surviving daughter of Louis XV.

A Childhood at Versailles, Chapter 2, Part 4 (2.4)

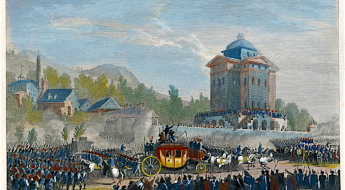

The little court of Mesdames the King’s aunts was a court within the court, referred to as the Old Court. Its habits were very regular. The princesses spent the whole summer at Bellevue, where their nephews and nieces constantly came for impromptu family dinners. A courier would arrive a few minutes ahead to announce them. When the courier was Monsieur’s, later Louis XVIII, the kitchen would be warned, and the dinner would be more ample and carefully presented. For the others, no warning was given, not even for the King, who had a large appetite, but was not nearly as much a gourmand as his brother.

At Bellevue, the royal family dined with everyone who happened to be there. With the people attached to Mesdames, their families, and a few regular guests, the number generally came to twenty or thirty persons.

Madame Adélaïde, by far the wittiest of Louis XV’s daughters, was agreeable and easy to live with in private, though extremely haughty. When a foreigner happened to call her Your Royal Highness, she flew into a rage, scolding the introducer of the ambassadors and even the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and held forth at length on these gentlemen’s incredible negligence. She insisted on being called Madame, and did not acknowledge that the Children of France took the style of Royal Highness.

She had a horror of wine, which she never drank, and people placed next to her at dinner turned away from her to drink it. Her nephews were always considerate of her in this way. If anyone failed in such consideration, she would say nothing, but he would never find himself near her at table again, and her lady in waiting would signal him to keep away from the princess. By humouring a few of her sensitivities, and above all by never spitting on the ground, which provoked her almost to abusiveness, one found that no one was easier to deal with.

Madame Adélaïde was the eldest of five princesses. She had not wanted to marry, preferring her status as a Daughter of France. She managed the Court until the death of Louis XV. She had been the friend and counsellor of her brother the Dauphin, and his memory was always very dear to her. She spoke of him constantly with the most tender affection.

One of her sisters, Madame Infante, reigned rather sadly in Parma; another, Madame Louise, was a Carmelite nun. Of the five princesses, this one had seemed by far the most worldly. She passionately loved all the earthly pleasures; she was a great gourmand, she was very concerned with her clothes, she had an extreme need for the most refined luxuries, she had quite a vivid imagination, and, finally, she was very much disposed to be coquettish. When the King entered Madame Adélaïde’s room to announce that Madame Louise had left Versailles during the night, the first thing she exclaimed was, ‘With whom?’ 14

The three remaining sisters never pardoned Madame Louise for keeping her intentions secret, and although they sometimes went to see her, it was without pleasure or intimate feeling. Her death caused them no regret.

It was not so with Madame Sophie. Mesdames Adélaïde and Victoire regretted her loss keenly and the intimacy of the two surviving sisters would have became still more tender if their two ladies-in-waiting, Mmes de Narbonne and de Civrac, had not made every effort to separate them, without ever quite being able to drive them apart.

Madame Victoire had very little wit but a great deal of goodness. It was she who said, with tears in her eyes, in a time of scarcity when the sufferings of the unfortunates doing without bread were under discussion, “But, my God, if they could only resign themselves to eating the crust.”15

At Bellevue, the residents lived communally, gathering to dine at two o’clock, then at five retiring to their own rooms until eight. At eight they returned to the drawing room, and after supper, the length of the evening would depend on how much or how little the company was enjoying itself. People would come from Paris and Versailles, and there would be a game of bingo after dinner.

It will not be hard to believe that the scores were rarely kept accurately, and at such gatherings several people were known to be the cause of this inaccuracy. Among others, there was a saintly bishop who was otherwise the most almsgiving of men, and an old marshal’s widow, in short enough culprits that my mother made up her mind always to play the same numbers, under the pretext of being occupied with her needlework, so that everyone knew her bet in advance. After the game, the princesses and their ladies worked on their embroidery in the drawing room, where there was a good deal of freedom for the others.

At Versailles, it was a quite a different life. Mesdames heard Mass separately, Madame Adélaïde in the Chapel, and Madame Victoire later in her oratory. They came together in the rooms of one or the other during the morning, but quite privately, and the two of them dined alone together. At six o’clock, Mesdames’ game took place in Madame Adélaïde’s rooms. It was then that one paid one’s court to them. The princes and princesses often attended this game, which was always bingo.

Notes:

14. Beneath the appearance of frivolity, if indeed it was as real as as Mme de Boigne seems to affirm, it is known that Madame Louise had already been practising secret austerities, mortifications and heroic virtues such as those of the Venerable Mother Thérèse de St. Augustin, at Versailles. There is reason to think that she had already offered herself, well before her entry into the Carmelite Order, which took place on 11 April, 1770, as an expiatory victim to save the soul of the King her father. Citation: Madame Louise de France, by Léon de la Brière, Paris, 1900.

15. To properly understand these words, so often quoted, and so decried since, it must be added that the good princess had a profound aversion to the crust and could never bring herself to eat it.

Part 2.5 will appear sometime during the week of 26 February-2 March, 2018.

Leave a Comment