Part 3.3 is the third of five parts of Chapter 3.

A Childhood at Versailles consists of the first 5 chapters of the memoirs of Mme de Boigne (1781-1866), née Adèle d’Osmond, who was a French salon hostess and writer. She was born in the Château de Versailles and lived at the court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette until her family fled to England during the Revolution. Later in her long life, she married a rich soldier of fortune 30 years her senior, hosted a brilliant salon in Paris, and became an intimate of the last French queen, Marie-Amélie, consort of King Louis Philippe (r. 1830-1848). Childless herself, Mme de Boigne addressed her memoirs to her grandnephew. The memoirs were not published until 1907, under the title Récits d’une tante, or An Aunt’s Tales. They’ve never been published in English, as far as I know, so I’ve decided to translate the first 5 chapters, the ones that take place mainly at Versailles, and post them here on this blog for interested readers to enjoy for free.

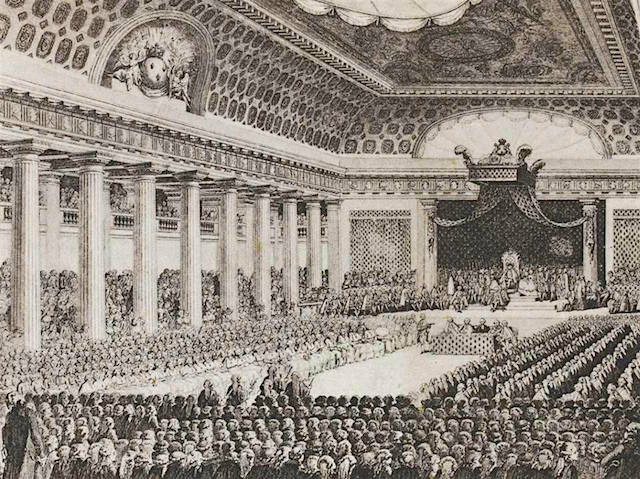

The chapters are quite lengthy, so I’ve broken each one into several parts. In Part 3.3, the author recounts her father’s refusal to attend the opening of the Estates General in May, 1789, and the offence he gave to Madame Adélaïde on that score.

A Childhood at Versailles, Chapter 3, Part 3 (Part 3.3)

My father made no mistake about the gravity of the circumstances. The ceremony of the opening of the Esates-General was solemn and accompanied by magnificent proceedings that attracted foreign visitors from every corner of Europe to Versailles. My mother, attired in full court dress, had my father informed that she was leaving. Not seeing him arrive, she went to his room and found him in his dressing gown.

“But you must hurry, we shall be late.”

“No, for I’m not going. I do not want to see that unfortunate man abdicate.”

That evening, Madame Adéläide spoke of the splendid view in the hall. She addressed my father with a few questions about the details. He replied that he had no idea of them.

“Where you were sitting, then?”

“I was not there, Madame.”

“Were you ill?”

“No, Madame.”

“How is it that when others have come from so far away to attend this ceremony, you did not trouble yourself to cross the street?”

“It is just that I do not like funerals, Madame, still less that of the monarchy.”

“And I do not like that at your age you think you know better than everyone else.”

So saying, the princess turned on her heels.

It should not be concluded from this that my father did not want concessions to be made. On the contrary, he was persuaded that the times demanded them imperiously, but he wanted them made according to a plan agreed upon in advance, and he wanted them to be generous and freely given, not extorted. He watched the Estates General open with mortal anguish because, abreast of everyone’s vague aims, he knew that no one had fixed the actual goal at which they had to stop, whether in terms of demands or in terms of concessions.

Furthermore, he had no confidence in M Necker. He believed that the latter was disposed to place the King at the top of a slope, not with the intention of pushing him down it, but with the arrogant notion that only he could hold him back, and thus render himself indispensable.

Madame Adélaïde’s anger did not have long to wait before events calmed it.

Part 3.4, in which Mme de Boigne recalls the events of October, 1789, should appear sometime in the first week of May, 2018.

Leave a Comment