Part 3.2 is the continuation of Chapter 3.

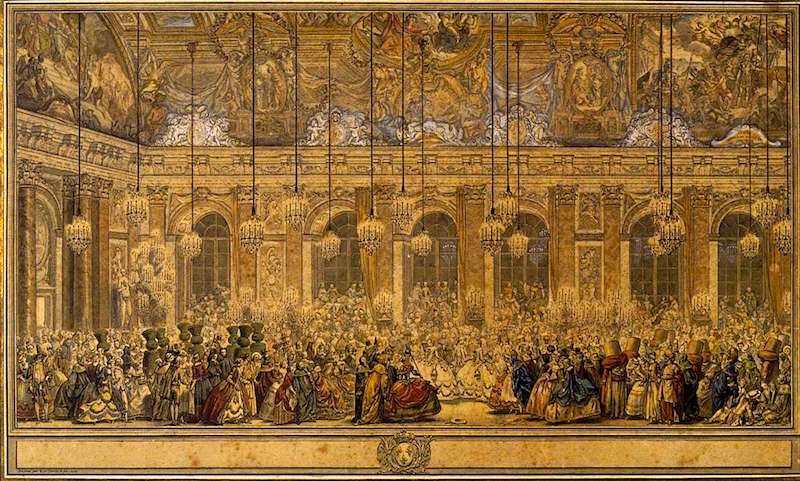

A Childhood at Versailles consists of the first 5 chapters of the memoirs of Mme de Boigne (1781-1866), née Adèle d’Osmond, who was a French salon hostess and writer. She was born in the Château de Versailles and lived at the court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette until her family fled to England during the Revolution. Later in her long life, she married a rich soldier of fortune 30 years her senior, hosted a brilliant salon in Paris, and became an intimate of the last French queen, Marie-Amélie, consort of King Louis Philippe (r. 1830-1848). Childless herself, Mme de Boigne addressed her memoirs to her grandnephew. The memoirs were not published until 1907, under the title Récits d’une tante, or An Aunt’s Tales. They’ve never been published in English, as far as I know, so I’ve decided to translate the first 5 chapters, the ones that take place mainly at Versailles, and post them here on this blog for interested readers to enjoy for free.

The chapters are quite lengthy, so I’ve broken each one into several parts. In Part 3.2, which is quite short, the author relates an anecdote involving Louis XVI and her pet dog, discusses her relationships with the royal children, and notes the darkening shadows of the oncoming Revolution.

A Childhood at Versailles, Chapter 3, Part 2 (3.2)

I often used to encounter the King in the gardens of Versailles, and no matter how far away he was when I spotted him, I always ran to him. When one day I failed to do so, he had me called. I arrived all in tears.

“What’s the matter, my little Adèle?”

“It’s your beastly guards, Sire, who want to kill my dog because he runs after your chickens.”

“I promise you that will never happen again.”

And indeed an order was issued to allow Mlle d’Osmond’s dog to chase the fowl.

My successes were no less great with the young generation. The Dauphin,20 who died at Meudon, loved me extremely, and incessantly asked for me to come play with him, and the Duc de Berry21 got himself in trouble because at a ball he only wanted to dance with me. Madame22 and the Duc d’Angoulême23 favoured me less.

The misfortunes of the Revolution put an end to my successes at Court. I do not know if they acted on me in the way of a homeopathic remedy, but it is certain that despite these beginnings of my life, I have never had the instincts of a courtier, nor a taste for the society of princes. Events had become too serious for anyone to be able to be amused by the antics of a child; 1789 had arrived.

Notes:

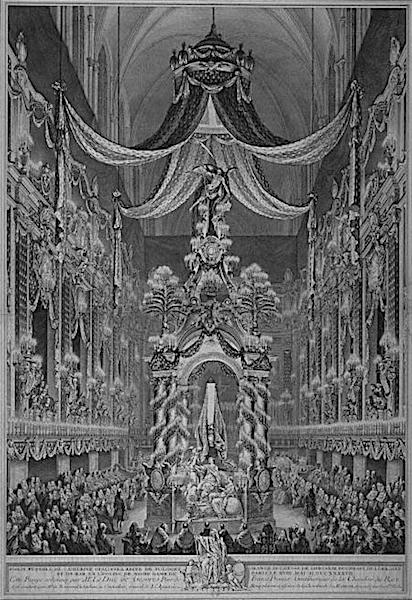

20. The first son of Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette; born in October, 1781, died in June, 1789.

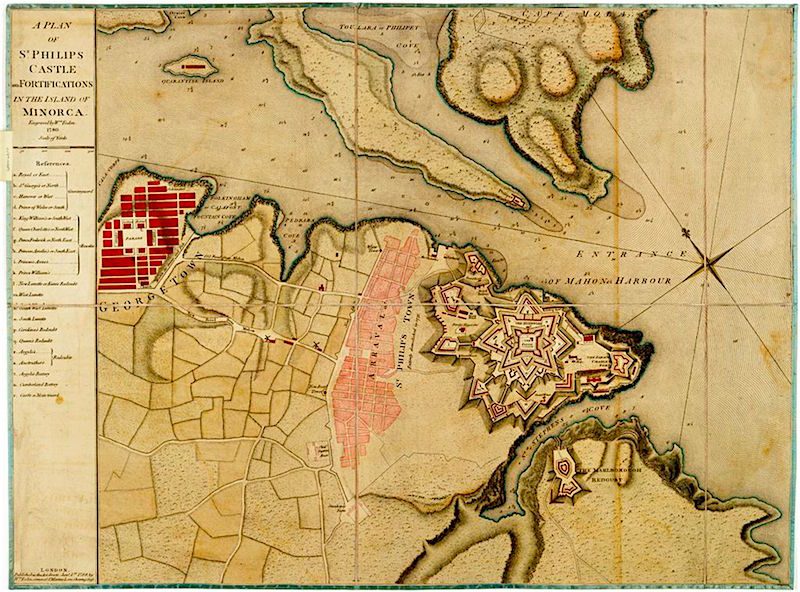

21. Charles-Ferdinand, second son of the Comte d’Artois, born in 1778.

22. Marie-Thérèse, daughter of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, born in 1778.

23. Louis-Antoine, eldest son of the Comte d’Artois, born in 1775.

Part 3.3 will deal with the opening of the Estates General and the events of October, 1789. Look for it here on the blog or on the Versailles Century Facebook page next week!