La Maréchale d’Aubemer, Nouvelle du XVIIIème Siècle, or The Widow of Field Marshal d’Aubemer: A Novella of the 18th Century, posthumously published in 1867, is a novel by the author and memoirist Madame de Boigne, born Adélaïde d’Osmond (1781-1866). Mine is the first English translation, available here for the first time anywhere.

In Chapter 14, the Maréchale, Gudule, and Henri are reunited at Magnanville.

THE WIDOW OF FIELD MARSHAL D’AUBEMER: A NOVELLA OF THE 18TH CENTURY

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Return to Magnanville

Seven months had passed since Lionel’s death; the old Marquis was still grieving the father of the great-grandchildren he had hoped for, and the Baronne her adored son, despite the embarrassment in which he had placed her. Not only had Lionel had spent all of his paternal inheritance, but she had had to make large sacrifices of her own fortune, to which her daughter-in-law renounced her rights.1 Gudule thus found herself once again the heiress to the slender means of the Saveuse battlements, but she also rediscovered the warblers and roses of her native mountains, as buoyant and fresh as she. Mme de Saveuse felt in the depths of her soul a wellspring of happiness unknown to her until then, which made her still more beautiful and revealed itself in her smallest actions. Since the confidences interrupted by such an unforeseen event, by which Gudule had been staggered, d’Estouteville’s name had passed neither the Maréchale’s lips nor her niece’s, but both thought of him ceaselessly, and the suspicion that the other was thinking of him was mutual. On the pretext of thanking Mme d’Aubemer for her goodness in asking for news of him, d’Estouteville had written to her and an increasingly active correspondence developed between them. His letters, like many others, were handed to Gudule, but she handed them back without comment. However, her aunt noticed that on those days her affection for her loved ones was even more effusive and her gaiety more free.

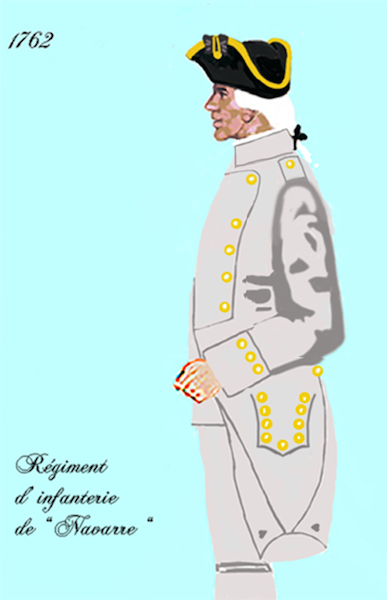

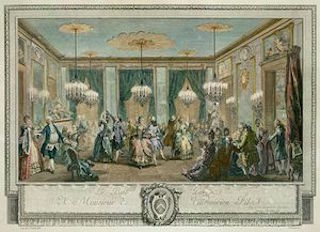

It was not without keen regret that Mme d’Aubemer decided to leave Saveuse; her long stay there had flowed past like a dream. Surrounded by attention and affection as she was, the days seemed much alike, but since they were diversified by varied occupations, they seemed to her to be sufficiently full. She almost admitted to herself that there comes a time of life when monotony is not dullness, but rather repose. The mountain air was good for her, and above all the feeling of isolation from which she usually suffered was held at bay; with her sister, she could speak of their youth and friends of times gone by; with Gudule, she could speak of her present relations. The old marquis himself had perfect recall, and, having served in the musketeers, linked his memories of former times with the Maréchale’s more recent ones, who thus felt herself growing younger in her own eyes. A number of neighbours, some of them rather likeable, frequently joined the family circle and soon enough seven months had passed very agreeably. All the same, the thought of spending the winter out of Paris horrified the Maréchale. Such a thing had never happened and seemed impossible to contemplate. Still, she delayed her departure from one day to another. The first snowfall brought home to her that she could no longer put off the fatal hour. She would very much have liked to take her niece with her, but Gudule wanted to finish her year of mourning at Saveuse, and the Maréchale very sadly had to concede that it was perhaps more suitable to do so.

Taking messages for various people, the Maréchale asked her, “Shall I say nothing to Henri d’Estouteville?”

“No, Aunt,” replied Gudule, blushing. “Not yet!” she replied in a lower voice, smiling gently.